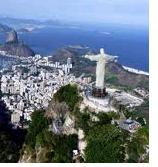

Rio de Janeiro

Brazil pushes environment projects to tackle crime and poverty

Brazil is set to host the 2016 Olympic Games, and is investing heavily in infrastructure and security to makes its streets cleaner and safer. New environment programs too could help lift people out of poverty.

Brazil is set to host the 2016 Olympic Games, and is investing heavily in infrastructure and security to makes its streets cleaner and safer. New environment programs too could help lift people out of poverty.

Rio is gearing up for the future. It's won the bid to host the 2016 Olympics, and before that, the 20th FIFA World Cup is scheduled to take place in the summer of 2014 in Brazil.

Posters celebrating these two historic events are everywhere, including at the scenic Guanabara Bay, where children play soccer on the beach next to groups of sunbathers. It's an idyllic scene, but one that doesn't tell the whole truth. There are two sides to Rio de Janeiro: behind the scenes of this popular tourist destination lie sprawling slums dominated by poverty and violence.

That didn't stop the International Olympic Committee (IOC) from choosing Rio as the site of the 2016 Olympics – making it the first city in South America to host the Games.

In its application, the Brazilian government laid out an extensive concept for the transformation of the city's infrastructure, set to cost $14 billion. As well as new sporting venues, the concept foresees new subway lines and extensions to the existing two airports and harbor.

Winners and losers

But 80 percent of the funds have been earmarked for Rio's more affluent neighborhoods. To Thomas Fatheuer from the German Heinrich Boell foundation, this makes the upcoming Olympics very much a mixed blessing.

"The poorer neighborhoods are left empty-handed," he complains. "It would make more sense to spend the money on long-term projects that are not necessarily tied to the Olympics."

That includes environmental programs. Although plans have been drawn up for the construction of new sewage treatment plants and the introduction of more efficient recycling facilities, there has been little follow-through, stresses Fatheuer.

Green and socially responsible

But Brazil does have an environmental agenda. In 2000, the government passed a law boosting energy efficiency, and electricity providers have long been required to invest 0.5 percent of their turnover in projects that promote energy-efficiency.

Half of these projects are designed to benefit the country's poor, who tend to spend over 25 percent of their income on electricity that is outdated and therefore far from cost-efficient.

Recent years have seen many residents of Rio's favelas given energy-saving lamps and new, cleaner refrigerators. According to the GTZ, the German Organization for Technical Cooperation, these consume half as much energy as old appliances. At the same time, they can be responsibly disposed of at new, environmentally-sound recycling plants.

Not only do such programs help Rio's working class economize, they also represent an opportunity for many to improve their situation. The refrigerator exchange program is often used by the people who spend their days collecting garbage – the catadores, which is Portugese for 'human scavenger' or 'rubbish collector.'

They used to collect old refrigerators in the favelas and dismantle them in order to recover and sell any valuable materials such as metals and plastics. Now, the government has managed to integrate these catadores in the new waste management system in a way that secures their livelihood and offers them a way out of illegality and crime.

Mean streets

Nonetheless, the streets of Rio are ruled by drug gangs, and clashes with police – known in Brazil to use routine violence themselves - are part of day-to-day life.

Security officers have been on permanent patrol in some slum neighborhoods for the last couple of years. These Polícia Pacificadora – or Peacemaker Police Units - have met with strong resistance from the gangs, but their presence is starting to show results, with crime rates beginning to fall.

In the run-up to the Olympics, Rio de Janeiro's authorities are planning to introduce these units in one hundred favelas. But this plan laid out by mayor Eduardo Paes has its detractors. According to Thomas Fatheuer, the only reason why the drug trade has fallen off in the patrolled neighborhoods is because the gangs have been squeezed out into other neighborhoods. All that's happened is that the problem has been relocated, he argues.

But the government is undeterred. "It's time to light the Olympic flame in a tropical country – and in the beautiful, wonderful city of Rio de Janeiro," rhapsodized then President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at the IOC conference in Copenhagen in 2009.

But until Rio cleans up its act – both socially and environmentally – its charm remains out of reach to much of its own population.

(Published by DW-World - January 4, 2011)