Climate change was recognized as a “common concern of humankind” in the late 80’s, under the UN General Assembly Resolution no. 43/53. From this moment on, discussions in the international community have intensified, resulting in the signature of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, in 1992, in Rio de Janeiro (Climate Convention, as we will refer from hereon). In 1997, the Climate Convention’s implementation was further detailed in the Kyoto Protocol, under which developed countries committed to quantified binding targets of GHG emissions reductions. Ever since that, climate science has evolved and has found that such efforts are not sufficient. Much more contributions are needed, by all parties, including the developing countries. As a result, the parties to the Climate Convention have decided to develop a new international climate agreement, to be signed by the end of 2015 in Paris. This is a work for lawyers, and it is not an easy one.

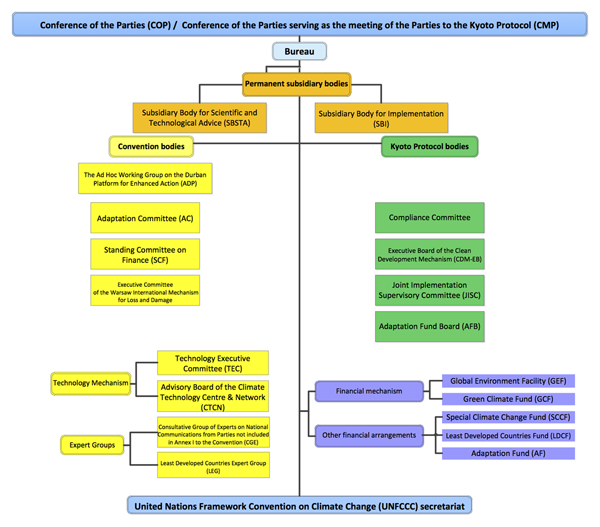

In 23 years of climate regime, 195 countries have been meeting at least 3 times a year, and have generated approximately 8000 documents, among submissions, reports and decisions of the Conference of the Parties. The Conference of the Parties (COP) – which resembles some sort of assembly of all the parties to the Convention – is the decision-making body. As the Kyoto Protocol entered into force, the parties to the Protocol too would gather in a meeting once a year, concomitant to the COP. This meeting became known as the COP/MOP. The COP and the COP/MOP meet simultaneously once by the end of each year, in order to discuss and deliberate issues of implementation of the Climate Convention and the Kyoto Protocol, in one of the largest international multilateral negotiations ever seen. Each decision has a binding effect over the parties, and therefore it is fundamental to know well all the decisions back in order to follow and participate in the current negotiations. Moreover, the Climate Convention is divided into dozens of bodies, committees and working groups, in a quite complex institutional architecture. See below:

Source: https://unfccc.int/bodies/items/6241.php

Since the Climate Convention is an international treaty, a better understanding of this requires some knowledge about the law of the treaties and public international law, as well as the ability to interpret the international law’s and contractual language, which are used in all decisions. In other words, just like in the negotiation of a high level private transaction, it is crucial to have a good lawyer to interpret the legal instrument and ensure that it is worded in the best language to serve its aimed purpose. It is also important to understand the Convention’s rules of procedure, which covers the voting rules, for instance, and may be often strategic in the negotiation.

Delegations from developed countries can count on the support of massive legal teams, graduated in the best universities in the world, experienced debaters, Harvard school negotiators. In case the negotiation round advances through the night out, there will be no problem: the diplomat negotiator in the roundtable can rely on night-shift legal counsels to recommend legal language that best suit the strategic position of the given developed country party.

It can be easily assumed though that this is not the reality for the developing countries, particularly the Least Developed Countries1 and the Small Island Developing States2. These countries come in very small delegations, so that they can barely follow the simultaneous multiple track negotiations. The delegates are public servants from the ministries of environment, science, agriculture. Most of the times, they are young fellows with little or no knowledge about the climate regime or the multilateral negotiations process. There are no lawyers whatsoever.

Ironically, these are exactly the countries that are most vulnerable to climate change. Some small islands in the Pacific, in the brink of extinction in case the ocean’s level rises, have already been looking for lands to purchase in other countries as a measure of reallocation of their people. Bangladesh, one of the Least Developed Countries in the world, faces the risk of immersion by floods, because of its extremely low-lying coast. In facts, this is already happening, as small islands between India and Bangladesh have disappeared in the recent years (and others are about to). But the sea level rise and the increase in the incidence of floods are just a few of the numerous possible impacts of global warming. Climate change affects the incidence of rainfall and wind patterns, as well as the maritime flows circulation, and the oceans acidity. This may cause droughts, floods, storms, heat waves, affecting soil fertility, marine and terrestrial biodiversity, and therefore causing tremendous impacts to food security, human health, local and regional economies and infrastructure, and ultimately leading to migrations of individuals and entire communities, as well as conflicts for land and natural resources3.

Consequently, in the focus of the negotiations, one of the most pressing issues is the “mitigation” of climate change, i. e. the measures to avoid the increase of greenhouse gases concentration in the atmosphere, which leads to the increase of the global temperatures. Currently we know that the global temperature’s increase cannot exceed 2o C compared with the pre-industrial era. If this temperature rise is exceeded, a tipping point may be reached, which will unchain other climate phenomena that will accelerate even more the warming process in an uncontrollable and irreversible way4. As a result, another extremely relevant negotiation theme is the “adaptation” to climate change, since we already know that some amount of warming will eventually happen thereby causing various impacts. In reality, climate change is already causing devastating impacts all around the world, including in developed countries. However, the adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change impacts of least developed countries and small island states is extremely limited. Therefore, it is in the utmost interest of these countries to address equally both of the issues – mitigation and adaptation, because for them these concerns transcend the negotiable: these are about the very survival of a nation’s people.

Noting with concern that the climate change roundtable is unbalanced, many international initiatives were raised to provide legal support and training to negotiators of vulnerable countries in the Climate Convention. An example of this is the Legal Response Initiative (LRI)5, a British not-for-profit organization, which offers its network of expert lawyers and academics to clarify legal queries and produce legal analysis and briefings on the climate change negotiation, providing pro bono legal support to vulnerable countries in the Climate Convention. The Legal Response Initiative also organizes legal workshops in loco, as it has done in Kenya, Bangladesh and other least developed countries. Moreover, the LRI provides free access to their legal opinions’ database, pursuant to a quick registration in the website. Within their network are legal practitioners from famous international firms, academics from prestigious universities and expert lawyers acting in the third sector, all over the world.

During the sessions in the Climate Convention, LRI sends a team of volunteer lawyers, to follow the negotiations and engage with the vulnerable countries’ delegations in order to provide real time legal assistance. If a more complex, research-demanding, query arises, the LRI’s liaison officer sends the matter to LRI’s office in London, based within the facilities of the international firm Simmons&Simmons. Upon the receipt of the legal query, the LRI’s office searches experts in its network who are able to respond the request on time. That way, LRI helps to level the playing field of the Climate Convention’s negotiations, enabling least developed countries to make their case and argue on equal footing with delegations from developed countries.

However, the challenge in 2015 is much greater than this. It is no longer about supporting countries with poor capacity in a complex multilateral negotiation. Now it is about designing a new international instrument, and such negotiation will require the resolution of a fundamental controversy between developed and developing countries: the matter of “who is going to pay the bill” on the fight against climate change. This is also an essentially legal discussion: it concerns the application of principles of public international law, environmental law and human rights. The most central of all these principles is the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities - inspired from the Rio Declaration and inserted in the Climate Convention –, which provides that developing countries bear differentiated (less) responsibility for addressing climate change than developed countries. Nevertheless, there is no clarity as of the measure of and the criteria for establishing such differentiated responsibility; and the rise of the emerging economies in the last decades has raised heated debates around the share of responsibility of developing countries, whose GHG emissions already surpass the developed countries’. On the other side, many developing countries insist that industrialized countries should bear the burden of their historical responsibility, since the current greenhouse gases atmospheric concentration traces back from since the beginning of the industrialization era, and this has made them well off. It is now clear that the success of a new climate agreement in Paris will depend on a consensus about the fair sharing of responsibilities in the fight against climate change.

The International Law Association (ILA) has established a committee to elaborate on Legal Principles Relating to Climate Change, formed by many acclaimed legal authors in the climate change field. Such works resulted in the Resolution n. 2/14, which proposes a Declaration of Legal Principles Relating to Climate Change6. The association presents a useful interpretation about the content of the legal principles in the Climate Convention and the application of other international law principles to the climate regime, including a recommendation for criteria in the application of the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities principle. Likewise, numerous academics, researchers and legal authors around the world have been devoted to the study of the concept of “climate justice”. Law Faculties from top-tier international universities have established climate law “labs”, with a view to produce legal outputs that may support public domestic policies and the UN climate negotiations, such as the Sabin Center for Climate Change, from the University of Columbia.

There are many other aspects of the elaboration of the new agreement that necessitate support from the legal community, such as the legal format and binding character of the new legal instrument, the legal nature of the “nationally determined contributions”7 that parties will present, the new agreement’s compliance mechanism and dispute resolutions mechanism, and so on. There is a great deal of engagement from the international legal community, but is this enough?

Most legal initiatives in the climate change field come from developed countries. Although there is substantial climate change activism, climate change legal research and the engagement of legal academics in the developing world is scarce. Nonetheless, in the case of Brazil there is great leadership potential, not only for the creation of state-of-the-art climate change policies, given the abundant renewable resources for clean energy, but also because of the very vocal performance of the Brazilian delegation in the history of the Climate Convention. Recently in the Geneva Conference, on February 2015, Brazil’s delegation had 09 active negotiators. Not bad. This by far outnumbers the delegations of Bangladesh or Vanuatu, both developing countries, represented by only 01 delegate. Judging by these numbers, climate change is a relevant agenda to Brazil, and there is substantive technical and legal capacity to address it. Then why don’t we have more climate change law labs in the universities? We should know better about climate change law at this point, and perhaps even assist less developed countries, starting by articulating with the South American neighbours, such as in initiatives like RESAMA (South American Network for Environmental Migrations).

Never climate change lawyers were so needed as they are now. Without a firm agreement in Paris, we will remain on track for a global temperature rise beyond the 2oC degrees, an irreversible point in the climate system, with disastrous consequences for the life of the current and future generations. This is the greatest challenge of our times, and the legal community must contribute to the solution of this problem. This is the legal support that matters now.